The History of Our Family by Julie Housner

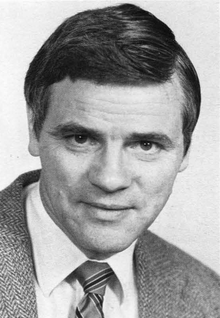

| Leroy Hood | |

|---|---|

Leroy Hood, in 2011. | |

| Born | (1938-10-10) October ten, 1938 Missoula, Montana |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Johns Hopkins Academy California Constitute of Technology |

| Known for | Scientific instrumentation for Dna sequencing & synthesis, Systems biology, P4 medicine |

| Spouse(south) | Valerie Logan[i] |

| Awards | Kyoto Prize (2002) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | biotechnology, genomics |

| Institutions | Institute for Systems Biological science, Caltech, Academy of Washington |

| Thesis | Immunoglobulins: Structure, Genetics, and Evolution(1968) |

| Doctoral counselor | William J. Dreyer |

| Doctoral students | Marking Yard. Davis, Trey Ideker, Jared Roach |

| Website | hood-price |

Leroy "Lee" Edward Hood (born October 10, 1938) is an American biologist who has served on the faculties at the California Plant of Engineering science (Caltech) and the University of Washington.[2] Hood has developed ground-breaking scientific instruments which fabricated possible major advances in the biological sciences and the medical sciences. These include the starting time gas phase protein sequencer (1982), for determining the sequence of amino acids in a given protein;[iii] [iv] a Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesizer (1983), to synthesize short sections of DNA;[3] [5] a peptide synthesizer (1984), to combine amino acids into longer peptides and curt proteins;[4] [half dozen] the get-go automated DNA sequencer (1986), to identify the club of nucleotides in DNA;[2] [seven] [8] ink-jet oligonucleotide technology for synthesizing DNA[nine] [10] and nanostring engineering for analyzing single molecules of DNA and RNA.[11] [12]

The protein sequencer, Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesizer, peptide synthesizer, and Deoxyribonucleic acid sequencer were commercialized through Practical Biosystems, Inc.[13] : 218 and the ink-jet technology was commercialized through Agilent Technologies.[9] [x] The automated DNA sequencer was an enabling technology for the Human Genome Project.[7] The peptide synthesizer was used in the synthesis of the HIV protease by Stephen Kent and others, and the evolution of a protease inhibitor for AIDS treatment.[6] [14] [15]

Hood established the offset cantankerous-disciplinary biology section, the Department of Molecular Biotechnology (MBT), at the University of Washington in 1992,[16] [viii] and co-founded the Constitute for Systems Biology in 2000.[eleven] Hood is credited with introducing the term "systems biological science",[17] and advocates for "P4 medicine", medicine that is "predictive, personalized, preventive, and participatory."[eighteen] [19] Scientific American counted him amidst the 10 most influential people in the field of biotechnology in 2015.[20]

Hood was elected a member of the National Academy of Engineering in 2007 for the invention and commercialization of fundamental instruments, notably the automated Deoxyribonucleic acid sequencer, that accept enabled the biotechnology revolution.

Background [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| | |

| | |

| |

Hood was born on October 10, 1938 in Missoula, Montana to Thomas Edward Hood and Myrtle Evylan Wadsworth.[21] and grew up in Shelby.[22] His father was an electrical engineer, and his mother had a degree in dwelling economics. Hood was i of four children, including a sister and two brothers, including a blood brother with Down's syndrome. Ane of his grandfathers was a rancher and ran a summer geology camp for university students, which Hood attended every bit a high school pupil. Hood excelled in math and science, being one of forty students nationally to win a Westinghouse Science Talent Search.[1] In addition, Hood played several high school sports and argue, the latter of which he would credit for his success in science advice later in his career.[23]

Education [edit]

Hood received his undergraduate educational activity from the California Institute of Engineering (Caltech), where his professors included notables such as Richard Feynman[17] and Linus Pauling.[13] [1] Hood received an M.D. from Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in 1964 and a Ph.D. from Caltech in 1968,[24] where he worked with William J. Dreyer on antibody diversity.[sixteen] Dreyer is credited with giving Hood two important pieces of advice: "If y'all want to do biology, practice information technology on the leading border, and if you want to exist on the leading edge, invent new tools for deciphering biological data."[25]

Career [edit]

In 1967, Hood joined the National Institutes of Health (NIH), to piece of work in the Immunology Branch of the National Cancer Institute as a Senior Investigator.[26]

In 1970, he returned to Caltech every bit an banana professor.[16] He was promoted to associate professor in 1973, full professor in 1975, and was named Bowles Professor of Biology in 1977. He served as chairman of the Division of Biology from 1980-1989 and manager of Caltech's Special Cancer Center in 1981.[21]

Hood has been a leader and a proponent of cross-disciplinary research in chemical science and biology.[16] In 1989 he stepped downwardly as chairman of the Division of Biological science to create and become manager of a newly funded NSF Science and Technology Eye at Caltech.[27] The NSF Center for the Evolution of an Integrated Protein and Nucleic Acid Biotechnology became one of the founding research centers of the Beckman Institute at Caltech in 1989.[28] [29] : 339–344 By this fourth dimension, Hood's laboratory included more than 100 researchers, a much larger group than was usual at Caltech. A relatively small school, Caltech was not well-suited to the creation of the blazon of large interdisciplinary enquiry organization that Hood sought.[30]

In October 1991, Hood appear that he would move to the University of Washington at Seattle, to institute and direct the get-go cross-disciplinary biology department, the Department of Molecular Biotechnology (MBT) at the University of Washington Medical Schoolhouse.[16] [viii] The new section was financed by a The states $12-million souvenir from Neb Gates, who shared Hood'due south involvement in combining biological research and computer engineering and applying them to medical research.[31] [32] Roger Perlmutter, who had worked in Hood's lab at Caltech earlier moving to UW as chair of the immunology department, played a key role organizing his recruitment to UW.[23] Hood and other scientists from Caltech'south NSF center moved to the University of Washington during 1992-1994, where they received renewed support from the NSF as the Center for Molecular Biotechnology.[27] [33] (Afterwards, in 2001, the Section of Molecular Biotechnology and the Genetics department at UW reorganized to course the Department of Genome Sciences.[34])

In 2000 Hood resigned his position at the University of Washington to become co-founder and president of the non-turn a profit Institute for Systems Biology (ISB),[35] perchance the offset independent systems biology system.[36] His co-founders were protein chemist Ruedi Aebersold and immunologist Alan Aderem.[37] Hood is still an affiliate professor at the University of Washington in Informatics,[38] Bioengineering[39] and Immunology.[forty] In April 2017, the ISB announced that Hood will be succeeded every bit president of ISB as of Jan 2018 by James Heath, while standing to lead his research grouping at ISB and serving on ISB's lath of directors.[37]

Hood believes that a combination of big data and systems biology has the potential to revolutionize healthcare and create a proactive medical approach focused on maximizing the health of the individual. He coined the term "P4 medicine" in 2003.[41] [42] In 2010 ISB partnered with the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in Columbus, Ohio to establish the nonprofit P4 Medicine Establish (P4MI). Its goal was stated as being "to lead the transformation of healthcare from a reactive organization to one that predicts and prevents illness, tailors diagnosis and therapy to the individual consumer and engages patients in the active pursuit of a quantified understanding of wellness; i.e. one that is predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory (P4)."[43] In 2012, P4 Medical Plant established an agreement with its first community health partner, PeaceHealth. PeaceHealth is a not-for-profit Catholic health care organisation, operating in a diverseness of communities in Alaska, Washington and Oregon.[44] [45] In 2016, ISB affiliated with Providence Health & Services,[46] and Hood became the senior vice president of Providence St. Joseph Wellness and its master scientific discipline officer.[37]

Hood has published more than 700 peer-reviewed papers, received 36 patents, and co-authored textbooks in biochemistry, immunology, molecular biological science, and genetics. In improver, he co-authored, with Daniel J. Kevles, The Code of Codes, a pop book on the sequencing of the human genome.[47]

He has been instrumental in founding 15 biotechnology companies,[11] including Amgen, Practical Biosystems, Systemix, Darwin, Rosetta Inpharmatics, Integrated Diagnostics, and Accelerator Corporation.[48] In 2015, he co-founded a startup chosen Arivale offering a subscription-based 'scientific wellness' service[49] which shut down in 2019.[l] While praising the quality of its offer, industry commentators attributed Arivale's closure to a failure to capture sufficient Customer lifetime value to create a profit from providing the service, suggesting that insufficient numbers of customers stuck with the information-driven, personalized dietary and lifestyle coaching information technology provided for long enough at a price point which would brand the concern model work.[51]

Inquiry [edit]

Genomics and proteomics [edit]

At Caltech, Hood and his colleagues created the technological foundation for the study of genomics and proteomics by developing five groundbreaking instruments - the protein sequencer (1982), the DNA synthesizer (1983), the peptide synthesizer (1984), the automatic DNA sequencer (1986) and later the ink-jet DNA synthesizer.[3] [52] [2] [7] [viii] Hood's instruments incorporated concepts of high throughput information accumulation through automation and parallelization. When applied to the report of poly peptide and Dna chemistries, these ideas were essential to the rapid deciphering of biological information.[52] [53] [54]

Hood had a strong involvement in commercial development, actively filing patents and seeking individual funding.[55] Applied Biosystems, Inc. (initially named GeneCo.) was formed in 1981 in Foster Urban center, California, to commercialize instruments developed by Hood, Hunkapiller, Caruthers, and others. The company was supported past venture capitalist William Grand. Bowes, who hired Sam H. Eletr and André Marion as president and vice-president of the new visitor. The company shipped the first gas phase protein sequencer, Model 4790A, in August 1982. The 380 Dna synthesizer was commercialized in 1983, the 430A peptide synthesizer in 1984, and the 370A Dna sequencing organisation in 1986.[56] [v]

These new instruments had a major impact on the emerging fields of proteomics and genomics.[three] [57] The gas-liquid phase protein sequencer was adult with Michael W. Hunkapiller, then a enquiry beau at Caltech.[24] [58] The instrument makes employ of the chemic process known equally the Edman degradation, devised by Pehr Edman.[58] Edman and Begg's 1967 design involves placing a protein or peptide sample into a spinning cup in a temperature controlled bedroom. Reagents are added to cleave the protein one amino acid at the time, followed by solvents to allow extraction of reagents and byproducts. A series of analysis cycles is performed to identify a sequence, one wheel for each amino acid, and the cycle times were lengthy.[59] Hood and Hunkapiller made a number of modifications, farther automating steps in the analysis and improving effectiveness and shortening wheel fourth dimension. By applying reagents in the gas stage instead of the liquid phase, the retention of the sample during the analysis and the sensitivity of the instrument were increased.[58] Polybrene was used as a substrate coating to improve anchor proteins and peptides,[60] and the purification of reagents was improved. HPLC analysis techniques were used to reduce analysis times and extend the technique'due south applicable range.[58] The corporeality of protein required for an assay decreased, from x-100 nanomoles for Edman and Begg's protein sequencer, to the low picomole range, a revolutionary increase in the sensitivity of the technology.[58] [61] [16] [62] The new sequencer offered significant advantages in speed and sample size compared to commercial sequencers of the time, the most popular of which were built by Beckman Instruments.[55] Commercialized as the Model 470A protein sequencer, it immune scientists to determine partial amino acid sequences of proteins that had not previously been accessible, characterizing new proteins and better agreement their activity, function, and furnishings in therapeutics. These discoveries had pregnant ramifications in biology, medicine, and pharmacology. [63] [v] [64]

The first automated DNA synthesizer resulted from a collaboration with Marvin H. Caruthers of the University of Colorado Boulder, and was based on Caruthers' work elucidating the chemistry of phosphoramidite oligonucleotide synthesis.[65] [66] [67] Caltech staff scientist Suzanna J. Horvath worked with Hood and Hunkapiller to acquire Caruthers' techniques in club to pattern a epitome that automated the repetitive steps involved in Caruthers' method for Dna synthesis.[68] [69] The resulting epitome was capable of forming brusque pieces of Dna called oligonucleotides, which could be used in DNA mapping and factor identification.[68] [5] The first commercial phosphoramidite DNA synthesizer was developed from this image past Practical Biosystems,[67] who installed the first Model 380A in Caruthers' lab at the Academy of Colorado in Dec 1982, earlier first official commercial shipment of the new musical instrument.[65] Revolutionizing the field of molecular biology, the Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesizer enabled biologists to synthesize Dna fragments for cloning and other genetic manipulations. Molecular biologists were able to produce DNA probes and primers for utilise in DNA sequencing and mapping, gene cloning, and cistron synthesis. The Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesizer played a critical role in the identification of many important genes and in the evolution of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the critical technique used to amplify segments of Deoxyribonucleic acid a million-fold.[v] [6]

The automated peptide synthesizer, sometimes referred to as a protein synthesizer, was developed by Hood and Stephen B. H. Kent, a senior research associate at Caltech from 1983 to 1989.[lxx] [69] The peptide synthesizer assembles long peptides and short proteins from amino acid subunits,[six] in quantities sufficient for subsequent analysis of their structure and function. This led to a number of significant results, including the synthesis of HIV-1 protease in a collaboration betwixt Kent and Merck and the assay of its crystalline construction. Based on this research, Merck developed an important antiprotease drug for the treatment of AIDS. Kent carried out a number of important synthesis and construction-function studies in Hood's lab at Caltech.[69]

Among the notable of the inventions from Hood's lab was the automated Dna sequencer. It made possible high-speed sequencing of the structure of Dna, including the man genome. It automated many of the tasks that researchers had previously done by hand.[30] [71] [72] Researchers Jane Z. Sanders and Lloyd M. Smith developed a style to color lawmaking the basic nucleotide units of DNA with fluorescent tags, greenish for adenine (A), yellowish-green for guanine (1000), orange for cytosine (C) and cherry-red for thymine (T).[73] Four differently colored fluorophores, each ane specific to a reaction with i of the bases, are covalently attached to the oligonucleotide primer for the enzymatic DNA sequence assay.[74] During the analysis, fragments are passed downwards through a gel tube, the smallest and lightest fragments passing through the gel tube first. A light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation light passed through a filter bicycle causes the bases to fluoresce. The resulting fluorescent colors are detected by a photomultiplier and recorded by a figurer. The first Deoxyribonucleic acid fragment to be sequenced was a common cloning vector, M13.[73] [75] [74]

The DNA sequencer was a critical technology for the Human Genome Project.[7] [74] Hood was involved with the Human Genome Project from its first coming together, held at the University of California, Santa Cruz, in 1985. Hood became an enthusiastic abet for The Human Genome Project and its potential.[1] [52] [76] [53] Hood directed the Human being Genome Middle's sequencing of portions of human being chromosomes 14 and 15.[77] [78] [79] [80] [81]

At the University of Washington in the 1990s, Hood, Alan Blanchard, and others adult ink-jet Deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis applied science for creating DNA microarrays.[82] [83] By 2004, their ink-jet Dna synthesizer supported high-throughput identification and quantification of nucleic acids through the creation of 1 of the first DNA array fries, with expression levels numbering tens of thousands of genes.[9] [84] Array analysis has become a standard technique for molecular biologists who wish to monitor gene expression.[84] Deoxyribonucleic acid ink-jet printer technology has had a significant bear on on genomics, biology, and medicine.[85] [86] [87]

Immunology and neurobiology [edit]

Hood too made generative discoveries in the field of molecular immunology. His studies of the amino acid sequences of immunoglobulins (also known equally antibodies) helped to fuel the 1970s' debate regarding the generation of allowed diversity and supported the hypothesis advanced by William J. Dreyer that immunoglobulin (antibody) chains are encoded by two separate genes (a abiding and a variable gene). He (and others) conducted pioneering studies on the structure and diversity of the antibiotic genes. This research led to verification of the "2 genes, one polypeptide" hypothesis and insights into the mechanisms responsible for the diversification of the immunoglobulin variable genes.[16] [88] [89] [90] [54] Hood shared the Lasker Honour in 1987 for these studies.[91]

Additionally, Hood was amid the first to study, at the gene level, the MHC (major histocompatibility complex) factor family[92] [93] and the T-cell receptor gene families[94] besides as beingness among first to demonstrate that culling RNA splicing was a key mechanism for generating alternative forms of antibodies. He showed that RNA splicing is the mechanism for generating the membrane bound and the secreted forms of antibodies.[95] [96]

In neurobiology, Hood and his colleagues were the starting time to clone and study the myelin basic protein (MBP) factor. The MBP is a central component in the sheath that wraps and protects neurons.[97] [98] Hood demonstrated that the condition chosen "shiverer mouse" arose from a defect in the MBP gene. Hood'south enquiry grouping corrected the neurological defect in mice (the shiverer defect) by transferring a normal MBP gene into the fertilized egg of the shiverer mouse. These discoveries led to extensive studies of MBP and its biology.[99]

Systems biological science and systems medicine [edit]

Offset in the 1990s, Hood focused more on cross-disciplinary biology and systems biology. He established in 1992 the first cross-disciplinary biological science department, the Molecular Biotechnology Department at the University of Washington.[31] [32] In 2000, he co-founded the Institute for Systems Biological science (ISB) in Seattle, Washington to develop strategies and technologies for systems approaches to biology and medicine.[11] [35] [36]

Hood pioneered the systems biology concept of considering human biology equally a "network of networks."[100] [101] In this model, understanding how systems function requires knowledge of: (1) the components of each network (including genetic, molecular, cellular, organ networks), (2) how these networks inter- and intra-connect, (3) how the networks alter over time and undergo perturbations, and (4) how function is achieved inside these networks.[102] At the ISB nether Hood's management, genomic, transcriptomic, metabolomic and proteomic technologies are used to understand the "network of networks" and are focused on diverse biological systems[103] (e.g. yeast, mice and humans).[104]

Hood applies the notion of systems biology to the written report of medicine,[105] [106] specifically to cancer[107] and neurodegenerative affliction.[108] His research article on a systems arroyo to prion diseases in 2009 was 1 of the first to thoroughly explore the apply of systems biology to interrogate the dynamic network changes in disease models. These studies are the beginning to explain the dynamics of diseased-perturbed networks and accept expanded to include frontal temporal dementia and Huntington'due south illness.[109] [110] Hood is also studying glioblastoma in mice and humans from the systems viewpoint.[111]

Hood advocates several practices in the burgeoning field of systems medicine, including: (one) The apply of family genome sequencing, integrating genetics and genomics, to identify genetic variants associated with wellness and affliction[112] (2) The utilize of targeted proteomics and biomarkers as a window into health and illness.[113] [114] He has pioneered the discovery of biomarker panels for lung cancer[115] and posttraumatic stress syndrome.[116] (3) The utilize of systems biology to stratify illness into its different subtypes assuasive for more effective treatment.[117] [54] (4) The use of systems strategies to identify new types of drug targets to facilitate and advance the drug discovery process.[107]

P4 medicine [edit]

Since 2002 Hood has progressively expanded his vision of the future of medicine: beginning focusing on predictive and preventive (2P) Medicine; then predictive, preventive and personalized (3P) Medicine; and finally predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory, also known as P4 Medicine.[118] Hood states that P4 Medicine is the convergence of systems medicine, big data and patient (consumer) driven healthcare and social networks.[117]

Hood envisions that by the mid-2020s each individual will exist surrounded by a virtual cloud of billions of information points and volition accept the computational tools to clarify this data and produce simple approaches to optimize wellness and minimize disease for each individual.[42] [53] [54] According to this view, the patient'due south demand for better healthcare will be the existent driving forcefulness for the credence of P4 Medicine by the medical community. This driving force is exemplified by the movement known equally the quantified self, which uses digital devices to monitor self-parameters such as weight, activity, sleep, nutrition, etc. His view is that P4 Medicine will transform the exercise of medicine over the next decade, moving it from a largely reactive, illness-care approach to a proactive P4 approach that is predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory.[117]

In 2010, Hood co-founded the P4 Medicine institute (P4Mi), for the development of Predictive, Preventive, Personalized and Participatory (P4) Medicine.[43] He argues that P4 Medicine will improve healthcare, subtract its toll and promote innovation.[119]

Awards and honors [edit]

Leroy Hood, 2008 Pittcon Heritage Award recipient

Dr. Lee Hood receiving the National Medal of Science from President Obama

Leroy Hood is a member of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS, 1982),[120] the National Academy of Engineering (2007),[121] and the National Academy of Medicine (formerly the Institute of Medicine, 2003).[122] He is one of but 15 scientists ever elected to all three national academies.[123] He is as well a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (1982),[124] a member of the American Philosophical Guild (2000),[125] a fellow of the American Order for Microbiology,[126] and a charter fellow of the National University of Inventors (2012).[127] [128] He has received 17 honorary degrees[11] from institutions including Johns Hopkins[129] and Yale University.[130]

In 1987 Hood shared the Albert Lasker Award for Basic Medical Enquiry with Philip Leder and Susumu Tonegawa for studies of the mechanism of immune diversity.[91] He later was awarded the Dickson Prize in 1988.[131] In 1987, Hood besides received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Accomplishment.[132]

He won the 2002 Kyoto Prize for Avant-garde Applied science for developing automated technologies for analyzing proteins and genes;[two] the 2003 Lemelson-MIT Prize for Innovation and Invention for inventing "four instruments that have unlocked much of the mystery of human biology" by helping decode the genome;[133] the 2004 Biotechnology Heritage Laurels;[134] [135] the 2006 Heinz Award in Technology, the Economy and Employment,[136] for breakthroughs in biomedical scientific discipline on the genetic level; inclusion in the 2007 Inventors Hall of Fame for the automated DNA sequencer;[137] the 2008 Pittcon Heritage Award for helping to transform the biotechnology industry;[138] [139] and the 2010 Kistler Prize for contributions to genetics that take increased knowledge of the man genome and its relationship to society.[18] Leroy Hood won the 2011 Fritz J. and Dolores H. Russ Prize "for automating DNA sequencing that revolutionized biomedicine and forensic science";[140] the 2011 National Medal of Science, presented at a White Firm anniversary by President Obama in early 2013;[141] the IEEE Medal for Innovations in Healthcare Technology in 2014,[9] and the 2016 Ellis Island Medal of Honor.[123] In 2017 he received the NAS Award for Chemical science in Service to Lodge.[8]

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d Hood, Leroy. "My Life and Adventures Integrating Biology and Technology: A Commemorative Lecture for the 2002 Kyoto Prize in Advanced Technologies" (PDF). Systems Biological science. Archived from the original on xvi July 2012. Retrieved 1 Dec 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c d "Leroy Edward Hood". Kyoto Prize . Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d Weingart, Peter; Stehr, Nico, eds. (2000). Practising interdisciplinarity. Toronto: University of Toronto printing. pp. 237–238. ISBN978-0802081391 . Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ a b Vanderkam, Laura (June sixteen, 2008). "Whatever knowledge that might be useful: Leroy Hood". Scientific American . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d due east Stephenson, Frank (2006). "Twenty-5 years of advancing science" (PDF). Applied Biosystems.

- ^ a b c d Hood, Leroy (October 2002). "A Personal View of Molecular Engineering and How It Has Inverse Biology" (PDF). Journal of Proteome Enquiry. ane (5): 399–409. CiteSeerX10.1.i.589.5336. doi:10.1021/pr020299f. PMID 12645911. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d Hutchison, C. A. (28 August 2007). "DNA sequencing: bench to bedside and beyond". Nucleic Acids Research. 35 (18): 6227–6237. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm688. PMC2094077. PMID 17855400.

- ^ a b c d e "2017 NAS Accolade for Chemical science in Service to Society Leroy Eastward. Hood". National Academy of Sciences . Retrieved one June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "IEEE Medal for Innovations in Healthcare Engineering science Recipients". IEEE . Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ a b Hamadeh, Hisham Grand.; Afshari, Cynthia A., eds. (2004). Toxicogenomics : principles and applications. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Liss. p. l. ISBN978-0-471-43417-7 . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d eastward "Leroy Hood, MD, PhD". Establish for Systems Biology . Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ Moore, Charles (April 7, 2015). "Doctor Anderson and NanoString Technologies To Jointly Develop Multi-Omic Assays Simultaneously Profiling Gene and Poly peptide Expression". Bio News Texas . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b Haugen, Peter (2007). Biology : decade by decade. New York: Facts On File. p. 216. ISBN9780816055302 . Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ "Agile HIV protease analog synthesized chemically". Chemical & Engineering News. 73 (nine): 38. 27 Feb 1995. doi:10.1021/cen-v073n009.p038.

- ^ Schneider, Jens; Kent, Stephen B.H. (July 1988). "Enzymatic activity of a synthetic 99 residue poly peptide corresponding to the putative HIV-1 protease" (PDF). Cell. 54 (3): 363–368. doi:x.1016/0092-8674(88)90199-vii. PMID 3293801. S2CID 46170353. Retrieved one June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f chiliad Gardiner, Mary Beth (2003). "Leroy Hood: Discovery Scientific discipline Biotech guru Leroy Hood leads researchers in a new direction". Lens: A New Way of Looking at Science . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b Rau, Marlene; Wegener, Anna-Lynn; Furtado, Sonia (2009). "New approaches to old systems: interview with Leroy Hood" (PDF). Science in School (12): 14–eighteen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Foundation For the Future to Award $100,000 Kistler Prize to Dr. Leroy Hood Five Inventions Laid Technological Foundation for Genomics and Proteomics". BusinessWire. May 6, 2010.

- ^ Carlson, Bob (2010). "P4 Medicine Could Transform Healthcare, but Payers and Physicians Are Non Yet Convinced". Biotechnology Healthcare. 7 (three): 7–eight. PMC2957728. PMID 22478823.

- ^ "The WorldView 100: Who are the virtually influential people in Biotech today?" (PDF). Scientific American WorldView: A Global Biotechnology Perspective. 2015. p. 5,10–11. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b Sleeman, Elizabeth (2003). The international who'south who 2004 (67 ed.). London: Europa. p. 750. ISBN9781857432176 . Retrieved iii June 2017.

- ^ Any knowledge that might be useful: Leroy Hood - Scientific American Retrieved 2017-07-28.

- ^ a b Timmerman, Luke D. (2016). Hood: Trailblazer of the Genomic Age. Tracy Cutchlow, Robert Simison. [Identify of publication not identified]. pp. 235–240, 7, 31. ISBN978-0-9977093-0-eight. OCLC 959626112.

- ^ a b "DNA Sequencing (RU 9549)". Smithsonian Institution Archives . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Hall, Bronwyn H.; Rosenberg, Nathan (2010). Handbook of the economic science of innovation (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Northward Holland. p. 229. ISBN9780080931111 . Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Yount, Lisa (2003). A to Z of biologists. New York: Facts on File. pp. 132–134. ISBN9780816045419 . Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Award Abstract #9214821 Science & Engineering Middle for Molecular Biotechnology". National Scientific discipline Foundation. November 24, 1999.

- ^ "Beckman Institute becomes physical" (PDF). Engineering & Science (Spring): 22–34. 1989. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Arnold Thackray & Minor Myers Jr. (2000). Arnold O. Beckman : one hundred years of excellence. foreword by James D. Watson. Philadelphia, Pa.: Chemic Heritage Foundation. ISBN978-0-941901-23-9.

- ^ a b "Medicine without frontiers". The Economist. September 15, 2005. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ a b Dietrich, Pecker (ix February 1992). "Futurity Perfect -- Thanks To Bill Gates' $12-Million Endowment, Scientist Leroy Hood Continues His Search For A New Genetic Destiny". The Seattle Times . Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ a b Herring, Angela (November six, 2012). "Biology is a circuitous thing". News @ Northwestern . Retrieved i December 2016.

- ^ Hanson, Susan L.; Lindee, M. Susan; Speaker, Elizabeth (1993). A guide to the Human Genome Projection : technologies, people, and institutions. Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 30. ISBN9780941901109 . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Collaborative Science Reveals Genome Secrets" (PDF). Genome Sciences, University of Washington . Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ a b Pollack, Andrew (April 17, 2001). "SCIENTIST AT WORK: LEROY HOOD; A Biotech Superstar Looks at the Bigger Moving picture". The New York Times . Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ a b Vermeulen, Niki (2010). Supersizing Science On Building Large-scale Enquiry Projects in Biology. Gardners Books. pp. 135–136. ISBN9781599423647 . Retrieved three June 2017.

- ^ a b c Hsiao-Ching Chou (2017-04-03). "Establish for Systems Biological science Recruits Technology Pioneer James Heath equally President". Institute for Systems Biology . Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "DR. LEROY Eastward. HOOD Curriculum Vitae" (PDF). Institute for Systems Biological science . Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ "Leroy E. Hood". Department of Bioengineering. Academy of Washington Schoolhouse of Medicine. Retrieved iii June 2017.

- ^ "Leroy Hood, M.D., Ph.D." Department of Immunology. University of Washington School of Medicine. Retrieved three June 2017.

- ^ Guest, Greg; Namey, Emily E. (2015). Public health research methods. Sage Pubns. p. 669. ISBN9781452241333 . Retrieved three June 2017.

- ^ a b Hood, Leroy; Flores, Mauricio (September 2012). "A personal view on systems medicine and the emergence of proactive P4 medicine: predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory" (PDF). New Biotechnology. 29 (half-dozen): 613–624. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2012.03.004. PMID 22450380. S2CID 873920. Retrieved iii June 2017.

- ^ a b Kirk, Sherri L. (May 14, 2010). "Ohio State Partners with Research Giant to Advance Health Intendance and Form P4 Medicine Establish". P4 Medicine Institute . Retrieved three June 2017.

- ^ PeaceHealth (15 March 2012). "P4 Medicine institute, PeaceHealth Launch Partnership to Pilot New Model in Health Intendance". PR Newswire . Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Timmerman, Luke (March 15, 2012). "Lee Hood's P4 Initiative Finds Customs Partner, PeaceHealth". Xconomy . Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Romano, Benjamin (March 14, 2016). "Institute for Systems Biology, Providence Squad Upward for Preventive Intendance". Xconomy . Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Hutchins, Shawn. "Systems biology pioneer Leroy Hood to nowadays at inaugural lectureship". Rice University . Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Philippidis, Alex (November 13, 2012). "Lucky 13 Series Entrepreneurs Meet the most enterprising people in biotech". Genetic Engineering science and Biotechnology News . Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ King, Anthony; O'Sullivan, Kevin. "New 'scientific wellness' strategy could cutting chronic illnesses and relieve coin". The Irish Times . Retrieved 2019-04-25 .

- ^ "Scientific wellness startup Arivale closes abruptly in 'tragic' end to vision to transform personal health". GeekWire. 2019-04-24. Retrieved 2019-04-25 .

- ^ "Closure of high-tech medical firm Arivale stuns patients: 'I feel as if one of my artillery was cut off'". The Seattle Times. 2019-04-26. Retrieved 2019-06-02 .

- ^ a b c "Rewriting Life Under Biology's Hood". MIT Applied science Review. September 1, 2001. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Hood, Leroy; Rowen, Lee (2013). "The human genome project: big science transforms biology and medicine". Genome Medicine. 5 (ix): 79. doi:x.1186/gm483. PMC4066586. PMID 24040834.

- ^ a b c d "Leroy Hood: At that place is going to be a fantastic revolution in medicine". Albert and Mary Lasker Foundation . Retrieved April x, 2017.

- ^ a b García-Sancho, Miguel (2012). Biology, computing, and the history of molecular sequencing : from proteins to Dna, 1945-2000. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN9780230250321 . Retrieved viii June 2017.

- ^ "The GeneCo Business Plan". LSF Magazine. Winter: 14–15. 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Patterson, Scott D.; Aebersold, Ruedi H. (March 2003). "Proteomics: the outset decade and across". Nature Genetics. 33 (3s): 311–323. doi:10.1038/ng1106. PMID 12610541. S2CID 9800076.

- ^ a b c d e Kinter, Michael; Sherman, Nicholas E. (2000). Protein sequencing and identification using tandem mass spectrometry. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience. pp. 13–14. ISBN9780471322498 . Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Lundblad, Roger L. (1995). Techniques in protein modification. Boca Raton, Flor.: CRC Press. pp. forty–41. ISBN9780849326066.

- ^ Hugli, Tony E. (January 1, 1989). Techniques in Poly peptide Chemical science. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc. p. 17. ISBN9781483268231 . Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Wittmann-Liebold, Brigitte (2005). "Reflections on the MPSA-Conferences : Evolution and Innovations of Poly peptide and Peptide Structure An alysis in the By xxx Years" (PDF). MPSA.

- ^ Hewick, RM; Hunkapiller, MW; Hood, LE; Dreyer, WJ (August ten, 1981). "A gas-liquid solid phase peptide and protein sequenator" (PDF). J Biol Chem. 256 (15): 7990–7. doi:x.1016/S0021-9258(18)43377-7. PMID 7263636. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ^ Marx, Jean Fifty. (1989). A Revolution in biotechnology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Printing. p. 12. ISBN9780521327497 . Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ Springer, Mark (2006). "Applied Biosystems: Celebrating 25 Years of Advancing Science" (PDF). American Laboratory News. May . Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b Caruthers, Thousand. H. (vi December 2012). "The Chemical Synthesis of Dna/RNA: Our Souvenir to Scientific discipline". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 288 (2): 1420–1427. doi:x.1074/jbc.X112.442855. PMC3543024. PMID 23223445.

- ^ Laikhter, Andrei; Linse, Klaus D. "The Chemic Synthesis of Oligonucleotides". Biosynthesis . Retrieved 9 June 2017.

- ^ a b Hogrefe, Richard. "A Short History of Oligonucleotide Synthesis". Trilink Biotechnologies . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ a b Emery, Theo. "Gene-mapping pioneer receive Lemelson-MIT prize". Associated Press . Retrieved April 24, 2003.

- ^ a b c Hood, Lee (July 2008). "A Personal Journey of Discovery: Developing Applied science and Changing Biology". Annual Review of Analytical Chemistry. 1 (1): ane–43. Bibcode:2008ARAC....1....1H. doi:x.1146/annurev.anchem.1.031207.113113. PMID 20636073.

- ^ "Stephen Kent". The Academy of Chicago . Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Perkel, Jeffrey (September 27, 2004). "An Automated Deoxyribonucleic acid Sequencer". The Scientist . Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "Caltech and the Man Genome Project". Caltech News. June 26, 2000.

- ^ a b Mathews, Jay (June 12, 1986). "Caltech's New DNA-Analysis Car Expected to Speed Cancer Research". The Washington Mail service . Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Smith, Lloyd M.; Sanders, Jane Z.; Kaiser, Robert J.; Hughes, Peter; Dodd, Chris; Connell, Charles R.; Heiner, Cheryl; Kent, Stephen B. H.; Hood, Leroy E. (12 June 1986). "Fluorescence detection in automatic Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence analysis". Nature. 321 (6071): 674–679. Bibcode:1986Natur.321..674S. doi:10.1038/321674a0. PMID 3713851. S2CID 27800972.

- ^ Smith, L Grand; Fung, S; Hunkapiller, M Westward; Hunkapiller, T J; Hood, Fifty E (April 11, 1985). "The synthesis of oligonucleotides containing an aliphatic amino group at the 5' terminus: synthesis of fluorescent Deoxyribonucleic acid primers for use in DNA sequence analysis". Nucleic Acids Research. 13 (7): 2399–2412. doi:ten.1093/nar/13.7.2399. PMC341163. PMID 4000959.

- ^ Gannett, Lisa (2012). "The Human Genome Projection". In Zalta, Edward Northward. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford, CA: Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

- ^ "NAS Honour for Chemistry in Service to Society". National Academy of Sciences . Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Brüls, Thomas; et al. (fifteen Feb 2001). "A concrete map of human chromosome 14". Nature. 409 (6822): 947–948. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..947B. doi:10.1038/35057177. PMID 11237018.

- ^ Lander, Eric S.; et al. (fifteen February 2001). "Initial sequencing and assay of the human genome" (PDF). Nature. 409 (6822): 860–921. Bibcode:2001Natur.409..860L. doi:ten.1038/35057062. PMID 11237011.

- ^ Heilig, Roland; et al. (1 January 2003). "The DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 14". Nature. 421 (6923): 601–607. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..601H. doi:10.1038/nature01348. PMID 12508121.

- ^ Zody, Michael C.; et al. (30 March 2006). "Analysis of the Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence and duplication history of human chromosome 15". Nature. 440 (7084): 671–675. Bibcode:2006Natur.440..671Z. doi:10.1038/nature04601. PMID 16572171.

- ^ Bumgarner, Roger (January 2013). "Overview of Deoxyribonucleic acid microarrays: Types, applications, and their future". Nucleic Acrid Arrays. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Vol. 101. pp. 22.1.1–22.one.11. doi:10.1002/0471142727.mb2201s101. ISBN978-0471142720. PMC4011503. PMID 23288464.

- ^ Blanchard, A.P.; Kaiser, R.J.; Hood, L.Due east. (January 1996). "High-density oligonucleotide arrays" (PDF). Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 11 (half-dozen–7): 687–690. doi:10.1016/0956-5663(96)83302-1. S2CID 13321733. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-13. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ a b Lausted, Christopher; Dahl, Timothy; Warren, Charles; King, Kimberly; Smith, Kimberly; Johnson, Michael; Saleem, Ramsey; Aitchison, John; Hood, Lee; Lasky, Stephen R (2004). "POSaM: a fast, flexible, open up-source, inkjet oligonucleotide synthesizer and microarrayer". Genome Biology. 5 (viii): R58. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-8-r58. PMC507883. PMID 15287980.

- ^ Kosuri, Sriram; Church building, George M (29 April 2014). "Big-scale de novo Dna synthesis: technologies and applications". Nature Methods. 11 (5): 499–507. doi:x.1038/nmeth.2918. PMC7098426. PMID 24781323.

- ^ Zhang, Sarah (November 20, 2015). "Cheap Dna Sequencing Is Here. Writing DNA Is Side by side". Wired . Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Hwang, Samuel James (2008). Deoxyribonucleic acid as a programmable textile : de novo cistron synthesis and mistake correction (Thesis). Massachusetts Plant of Technology. hdl:1721.1/44423.

- ^ Nossal, Gustav J. V. (23 Jan 2003). "The double helix and immunology". Nature. 421 (6921): 440–444. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..440N. doi:10.1038/nature01409. PMID 12540919.

- ^ Rees, Anthony R. (2015). The Antibody Molecule: From Antitoxins to Therapeutic Antibodies. Oxford Academy Press. pp. 104–120. ISBN978-0199646579 . Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Hood, 50.; Davis, One thousand.; Early, P.; Calame, Chiliad.; Kim, S.; Crews, Southward.; Huang, H. (1981). "2 types of DNA rearrangements in immunoglobulin genes". Cold Leap Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 45 (2): 887–898. doi:10.1101/sqb.1981.045.01.106. PMID 6790221. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ a b "1987 Albert Lasker Bones Medical Inquiry Award Genetic basis of antibody variety". Albert And Mary Lasker Foundation built by blenderbox . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ Hood, Leroy; Steinmetz, Michael; Goodenow, Robert (April 1982). "Genes of the major histocompatibility complex" (PDF). Cell. 28 (4): 685–687. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(82)90046-0. PMID 6284368. S2CID 41098069. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Hood, L; Steinmetz, M; Malissen, B (April 1983). "Genes of the Major Histocompatibility Circuitous of the Mouse". Annual Review of Immunology. 1 (one): 529–568. doi:x.1146/annurev.iy.01.040183.002525. PMID 6152713.

- ^ Glusman, Gustavo; Rowen, Lee; Lee, Inyoul; Boysen, Cecilie; Roach, Jared C.; Smit, Arian F.A.; Wang, Kai; Koop, Ben F.; Hood, Leroy (September 2001). "Comparative Genomics of the Human and Mouse T Prison cell Receptor Loci". Immunity. 15 (3): 337–349. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00200-10. PMID 11567625.

- ^ Eastward, Zhiguo; Wang, Lei; Zhou, Jianhua (30 September 2013). "Splicing and alternative splicing in rice and humans". BMB Reports. 46 (9): 439–447. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.9.161. PMC4133877. PMID 24064058.

- ^ Early, P; Rogers, J; Davis, M; Calame, K; Bond, Thousand; Wall, R; Hood, L (June 1980). "Two mRNAs tin be produced from a unmarried immunoglobulin ? gene by alternative RNA processing pathways". Prison cell. twenty (2): 313–319. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(fourscore)90617-0. PMID 6771020. S2CID 39580237.

- ^ Kamholz, J; Spielman, R; Gogolin, K; Modi, Westward; O'Brien, Southward; Lazzarini, R (1987). "The homo myelin-basic-poly peptide gene: chromosomal localization and RFLP assay". Am J Hum Genet. 40 (4): 365–373. PMC1684086. PMID 2437795.

- ^ Saxe DF, Takahashi Due north, Hood 50, Simon MI (1985). "Localization of the human myelin basic protein gene (MBP) to region 18q22----qter by in situ hybridization". Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 39 (4): 246–9. doi:10.1159/000132152. PMID 2414074.

- ^ Walters, LeRoy; Palmer, Julie Gage (1996). The ethics of human gene therapy. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN9780195059557 . Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "Hood Delivers Rodbell Lecture, Mar. 10". NIH Record. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ "Life Science Innovation in Seattle is at the Top of its Game". AYOGO. June xiv, 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Nass, Sharyl J.; Wizemann, Theresa, eds. (2012). "Chapter 3: Informatics and Personalized Medicine". INFORMATICS NEEDS AND CHALLENGES IN CANCER Inquiry Workshop Summary. Washington, D.C.: NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS. pp. 31–42. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- ^ Wang, Daojing; Bodovitz, Steven (June 2010). "Single cell analysis: the new borderland in ?omics?". Trends in Biotechnology. 28 (6): 281–290. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.03.002. PMC2876223. PMID 20434785.

- ^ Hood, Leroy; Koop, Ben; Goverman, Joan; Hunkapiller, Tim (1992). "Model genomes: The benefits of analysing homologous human and mouse sequences". Trends in Biotechnology. 10 (one–2): 19–22. doi:x.1016/0167-7799(92)90161-North. PMID 1367926.

- ^ Wolkenhauer, Olaf; Auffray, Charles; Jaster, Robert; Steinhoff, Gustav; Dammann, Olaf (eleven January 2013). "The road from systems biology to systems medicine". Pediatric Research. 73 (4–2): 502–507. doi:10.1038/pr.2013.iv. PMID 23314297.

- ^ Auffray, Charles; Chen, Zhu; Hood, Leroy (2009). "Systems medicine: the future of medical genomics and healthcare". Genome Medicine. 1 (i): 2. doi:x.1186/gm2. PMC2651587. PMID 19348689.

- ^ a b Tian, Q.; Price, N. D.; Hood, 50. (February 2012). "Systems cancer medicine: towards realization of predictive, preventive, personalized and participatory (P4) medicine". Journal of Internal Medicine. 271 (2): 111–121. doi:ten.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02498.ten. PMC3978383. PMID 22142401.

- ^ Lausted, Christopher; Lee, Inyoul; Zhou, Yong; Qin, Shizhen; Sung, Jaeyun; Cost, Nathan D.; Hood, Leroy; Wang, Kai (6 Jan 2014). "Systems Arroyo to Neurodegenerative Illness Biomarker Discovery". Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 54 (1): 457–481. doi:10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-011613-135928. PMID 24160693.

- ^ Omenn, Gilbert Due south (24 March 2009). "A landmark systems assay of prion illness of the encephalon". Molecular Systems Biological science. 5: 254. doi:x.1038/msb.2009.12. PMC2671917. PMID 19308093.

- ^ Hwang, Daehee; Lee, Inyoul Y; Yoo, Hyuntae; Gehlenborg, Nils; Cho, Ji-Hoon; Petritis, Brianne; Baxter, David; Pitstick, Rose; Immature, Rebecca; Spicer, Doug; Price, Nathan D; Hohmann, John 1000; DeArmond, Stephen J; Carlson, George A; Hood, Leroy Eastward (24 March 2009). "A systems arroyo to prion disease". Molecular Systems Biological science. 5: 252. doi:10.1038/msb.2009.10. PMC2671916. PMID 19308092.

- ^ Ghosh, Dhimankrishna; Funk, Cory C.; Caballero, Juan; Shah, Nameeta; Rouleau, Katherine; Earls, John C.; Soroceanu, Liliana; Foltz, Greg; Cobbs, Charles S.; Toll, Nathan D.; Hood, Leroy (May 2017). "A Cell-Surface Membrane Poly peptide Signature for Glioblastoma". Cell Systems. 4 (5): 516–529.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cels.2017.03.004. PMC5512565. PMID 28365151.

- ^ Roach, J. C.; Glusman, G.; Smit, A. F. A.; Huff, C. D.; Hubley, R.; Shannon, P. T.; Rowen, L.; Pant, K. P.; Goodman, Northward.; Bamshad, Yard.; Shendure, J.; Drmanac, R.; Jorde, L. B.; Hood, L.; Galas, D. J. (10 March 2010). "Analysis of Genetic Inheritance in a Family Quartet past Whole-Genome Sequencing". Science. 328 (5978): 636–639. Bibcode:2010Sci...328..636R. doi:x.1126/scientific discipline.1186802. PMC3037280. PMID 20220176.

- ^ Mustafa, Gul Thousand (2015). "Targeted proteomics for biomarker discovery and validation of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C infected patients". Earth Journal of Hepatology. 7 (ten): 1312–24. doi:10.4254/wjh.v7.i10.1312. PMC4450195. PMID 26052377.

- ^ Veenstra, T. D. (25 January 2005). "Biomarkers: Mining the Biofluid Proteome". Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. four (iv): 409–418. doi:10.1074/mcp.M500006-MCP200. PMID 15684407.

- ^ Zeng, Xuemei; Hood, Brian L.; Sun, Mai; Conrads, Thomas P.; Day, Roger S.; Weissfeld, Joel 50.; Siegfried, Jill M.; Bigbee, William L. (3 December 2010). "Lung Cancer Serum Biomarker Discovery Using Glycoprotein Capture and Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry". Journal of Proteome Enquiry. ix (12): 6440–6449. doi:10.1021/pr100696n. PMC3184639. PMID 20931982.

- ^ "'Decoding DNA: The Future of Deoxyribonucleic acid Sequencing': Dr. Lee Hood Appears on Australian Radio Testify". Institute for Systems Biology. 2014-02-28. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ a b c Flores, Mauricio; Glusman, Gustavo; Brogaard, Kristin; Price, Nathan D; Hood, Leroy (August 2013). "P4 medicine: how systems medicine volition transform the healthcare sector and club". Personalized Medicine. 10 (6): 565–576. doi:10.2217/PME.thirteen.57. PMC4204402. PMID 25342952.

- ^ Hunt, Dave. "Tampa Stakes Its Merits to Lead Healthcare into the Hereafter". The Doctor Weighs In. Archived from the original on September 1, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2013.

- ^ Strickland, Eliza (29 Baronial 2014). "Medicine'south Side by side Large Mission: Understanding Wellness". IEEE Spectrum . Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "Leroy Eastward. Hood". National University of Sciences . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Dr. Leroy Hood". National Academy of Engineering . Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "National Academy of Medicine". University of Washington . Retrieved ii June 2017.

- ^ a b "Dr. Lee Hood Receives Ellis Island Medal of Honor". Institute for Systems Biology. 21 April 2004. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ "American University of Arts and Sciences". University of Washington . Retrieved ii June 2017.

- ^ "American Philosophical Society". University of Washington . Retrieved ii June 2017.

- ^ "ASM News". American Lodge for Microbiology. Archived from the original on 11 Nov 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "National Academy of Inventors 2012 Charter Fellow: Dr. Lee Hood". ISB News. 2012-12-18. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "National Academy of Inventors congratulates NAI Fellows Robert Langer and Leroy Hood, and NAI Member James Wynne on receiving U.S. National Medals". USF Research News. University of South Florida. Jan eight, 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees Awarded". Johns Hopkins Academy. Archived from the original on 21 February 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Honorary Caste Citations Commencement 2009". Yale News. May 25, 2009. Retrieved two June 2017.

- ^ "Dickson Prize : Past Winners". Carnegie Mellon University . Retrieved ii June 2017.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Leroy Hood". Lemelson-MIT Plan . Retrieved 1 Dec 2016.

- ^ "Biotechnology Heritage Award". Scientific discipline History Institute. 2016-05-31. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ "Leroy Hood to receive 2004 Biotechnology Heritage Award". Eureka Alert. May 26, 2004. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "Dr. Leroy Hood". The Heinz Awards . Retrieved 1 Dec 2016.

- ^ National Inventors Hall of Fame (February 8, 2007). "National Inventors Hall of Fame announces 2007 inductees". Eureka Alert . Retrieved one June 2017.

- ^ "Pittcon Heritage Accolade". Science History Plant. 2016-05-31. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Wang, Linda (March 24, 2008). "Pittcon Awards 2008". Chemical & Technology News. 86 (12): 67–68. Retrieved ane June 2017.

- ^ "Fritz J. and Dolores H. Russ Prize". National Academy of Technology . Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ "The President's National Medal of Scientific discipline: Recipient Details". National Science Foundation . Retrieved 1 June 2017.

External links [edit]

- Articles for Leroy Hood, at the Constitute for Systems Biology

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leroy_Hood

0 Response to "The History of Our Family by Julie Housner"

Post a Comment